“Give us back abundant and cheap energy” says Samuele Furfari, Professor of Geopolitics of Energy, Senior retired European Commission official, President of the European Society of Engineers and Industrialists

Doctor of Applied Sciences, Polytechnic Engineer

In the early 1970s, all was well in the European Community – as the EU was then called. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the reconstruction of a battered Europe was made possible by the Marshall Plan, named after the Secretary of State for International Relations of the US government. A massive $19 billion in financial aid has been distributed to the European states of the OECD, the organisation created in 1948. The choice of beneficiary companies for the supply of equipment was left to the States alone, but aid steering committees defined the priority sectors.

The calm before the storm

The Marshall Plan, the European people’s hard work, who aspired to a good quality of life after the suffering inflicted by the war, led the whole of Western Europe redoubling efforts and success. GDP growth between 1950 and 1970 was about 4% per year. These years of prosperity in all industrial and domestic fields are called the ‘Glorious Thirty’. Women no longer have to do laundry manually, the mechanisation of agriculture relieves agricultural workers, leisure becomes possible for all. It was also made possible by the abundant and cheap energy that kept the economy running at full capacity. This full employment made it easy to change jobs. My brother-in-law explains that it was possible to change jobs because another one was offered at a few cents more per hour.

At that time, oil, cheap and easy to use, replaced coal. When the European Coal and Steel Community was created in 1950, coal accounted for 80% of the energy consumption of the Six. This figure fell to 65% in 1960 and 30% in 1970 (it is now 12%). The European Community, which was energy independent, was thus gradually becoming dependent on the outside world, on a new source of energy and in a region of the world, the Middle East. But who cares? The security of energy supply was indeed mentioned in 1968 in an initial European Commission document entitled ‘First orientation of the European Community’s energy policy’. It proposed medium-term forecasts and guidelines for each energy source, the establishment of a common market, which implies the implementation of common rules, the implementation of a policy of secure and cheap supply, and the establishment of research and development programmes in hydrocarbons (the ECSC Treaty already provided for coal and Euratom for nuclear energy). As its title indicated, it was only guidance, it was not a question of implementation. It took the abrupt awakening of the oil shocks for these ideas to be applied.

Note that the term ‘cheap’ appears seven times in this strategy document. It was in line with the Messina Resolution of June 1955, in which the concept of abundant and cheap energy was inscribed, it constitutes one. Said: ‘The achievement of cheap supply means the search for the cost of supply at the lowest level, this cost being understood in the broad sense of the expenditure that the community must make to cover its energy needs. […] the consumer needs indicators that are as clear as possible, which in the market economy are prices.’ This is the opposite of what today’s European leaders want: expensive energy to limit its use to decarbonise the world. The elders of the European Commission no longer recognise this.

The two oil shocks

The Six-Day War in June 1967 gave Israel a clear victory over its Arab neighbours, the war emblem being the capture of East Jerusalem and the Kotel. In revenge, in 1973, on the fast day of Yom Kippur, a public holiday in Israel, which coincided in 1973 with the period of Ramadan, the Egyptians and Syrians attacked by surprise simultaneously in the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. After being surprised for several days, Israel regained control of the situation, reconquered the Golan Heights and rushed towards Damascus and the Egyptian Sinai. At the instigation of Muammar Gaddafi, the other Arab countries reacted. The Libyan colonel is in trouble in his country because his coup has driven away the oil companies and the revenues, he relied on to succeed in his seizure of power are disappearing. He wants to raise the price of oil. On December 25 (!) 1973, the Arab Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEP) decided to limit its oil exports by 5% per month for all countries. However, countries ‘pro-Israel’, such as the United States, the Netherlands and Portugal, are subject to a total embargo.

The impact on the economy of the European Community is considerable. Oil consumption was rationed and, symbolically, the governments of the Community decided to organise ‘car-free Sundays’, the first of which was organised on 18 November 1973. At the time, a litre of leaded gasoline cost about a quarter of a euro.

Economic growth was severely affected; after 1973, it fell to an average of 2.5% and never returned to its highest level. It was no longer a question of abundant and cheap energy and therefore no longer of sustained growth. So there was a price crisis and a supply crisis. Moreover, this crisis, unlike today was global, since the Arab decisions disrupted the oil market, which is unique in the world.

The OECD is responding to the Arab countries’ attempt at geopolitical control.

OECD countries could not tolerate this control over both their economies and their international relations, as it was an attempt to sanction support for Israel. They organise themselves quickly. Henry Kissinger, who was the US Secretary of State at the time, proposed the creation of an agency specialising in energy. Its members will be obliged to have reserves of crude oil or petroleum products equivalent to three months’ consumption or two months’ imports, these reserves being held in whole or in part by the Member State or by private companies. These strategic stocks are a real weapon of retaliation and are always capable of silencing any attempt at an embargo. In three months, Member States have time to organise themselves and ‘Car-Free Sundays’ are a distant memory that today’s young people cannot even imagine.

This organisation, which is called the International Energy Agency (IEA), is known across the Atlantic as the ‘oil watchdog’. Georges Brondel, who was director of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Energy, convinced the Americans to choose Paris, which was already the headquarters of the OECD, so as not to give the agency an American image. He also convinced Washington to add to the agency’s mandate for the organisation of dialogue between oil producers and consumers. For years, the IEA has been the reference for analysing the global energy situation. Its annual energy outlook was a highly valued reference.

The International Energy Agency has played an extraordinary role until recently. However, in recent years, it has become one of the champions of decarbonisation and more particularly for the promotion of renewable energies at all costs. The International Energy Agency, which was the watchdog of oil, is now inviting oil companies to change their profession, no more and no less…

Critics are beginning to be heard, even if they have existed for a long time as an aside. Standard and Poor’s reports that OPEC considers that ‘the IEA has compromised its technical analysis to fit its narrative’. The British think tank, also called IEA, but standing for the Institute of Economic Affairs, published a vitriolic article entitled ‘The defunct International Energy Agency’: ‘To be clear, from a free market or environment, this policy is foolish […]. To say that the IEA […] is a stereotype of global elitists is to underestimate the problem.’

COCONUC, the European Community’s threefold response

Nuclear

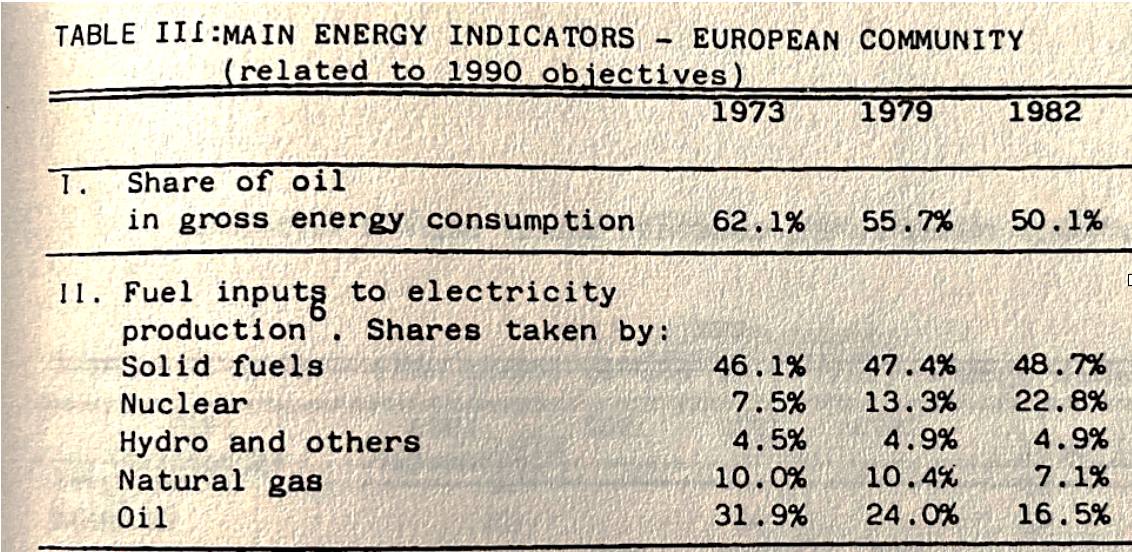

The Euratom Treaty of 1958 launched the nuclear adventure in the EU. At a time when the Arab countries are launching their offensive, nuclear power is becoming a strong reality. Arab strategists did not foresee this. Very quickly, in France, Germany, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Sweden, etc., the oil used to produce electricity was replaced by nuclear energy. In a chapter I wrote for a book published by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, I presented the following table. It shows the extraordinary reduction in oil consumption in power plants. In nine years, the share of oil in the primary energy balance has fallen from 62% to 50%, but especially oil, which accounted for 32% of primary energy in power plants, has fallen to 16%. The main change is the share of nuclear energy, which rose from 7% to 23%. Nuclear power came at the right time. There, there was an energy transition!

Russian gas used in power plants could also suffer the same fate as Arab oil in the 1970s and 1980s, leaving aside the illusion that renewables can lead to the energy transition.

Coal

The other policy that has helped get us back on track is the promotion of coal burning. Coal had been burned for two centuries, but in a rustic way, with an impact on the environment that was then, and is now, rightly considered unacceptable. So a vast modern coal burning program called Clean Coal Technology was launched. I had the privilege of being the leader of this program, which has developed clean coal technologies that significantly reduce all air pollutants (SO₂, NOx, dust and fly ash) while reducing unburnt. It was so avant-garde that the Chinese copied these technologies and now sell such plants in Africa, Asia, and the Balkans.

Some might consider this an anachronistic idea, but it is not. This energy is expanding considerably in the world: when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Rio de Janeiro,1992) was adopted, the world consumed 92 million tonnes. In 2021, consumption increased to 160 Mt. Countries that care about their growing population by creating jobs and added value use this abundant and cheap energy, unlike the EU. For example, on the EU’s doorstep, the Balkans exploit their indigenous coal and lignite reserves: coal is the almost exclusive source of Kosovo’s electricity generation (95%); Serbia (70%) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (68%) rely more on coal for their electricity production than China (61%)!

Energy savings

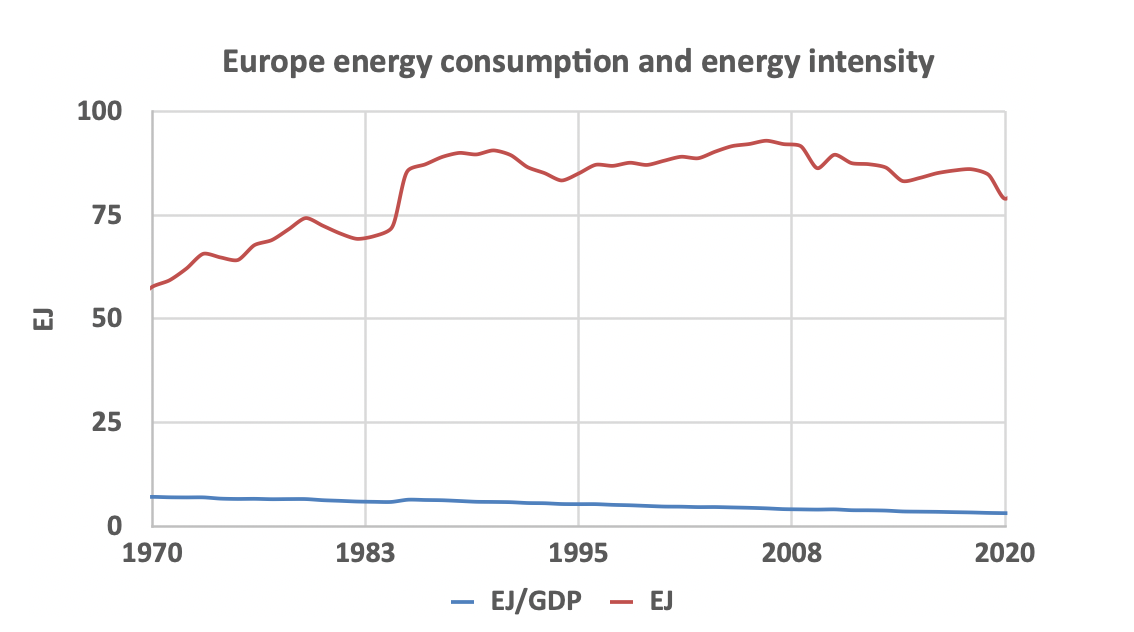

The fashion for energy sobriety is not new. It is only the name that is new, making us believe that human behaviour can compensate for the inelasticity of energy demand. At the time, we talked about energy saving with a well-known slogan ‘In France, we do not have oil, but we have ideas’, ideas to save energy. These friendly and generous methods did not reduce the growth in energy demand. Admittedly, the parameter that matters – energy intensity, which measures energy consumption per unit of GDP produced – has fallen. This shows, on the one hand, that it is the technology that has made it possible to progress and above all those companies have put in place energy efficiency policies not to save the planet, but to succeed in the world of competitiveness.

The English preferred to speak of ‘conservation of energy’ so that the combination of the words coal, conservation and nuclear made it possible to create the acronym of the COCONUC strategy.

There was also another, lesser-known component of the strategy, which we will discuss in the next section.

The Oil and Gas Demonstration Program

The Community’s hydrocarbon project programme was one of the European Community’s first concrete responses to the energy supply crisis of 1973. The objective of this programme was to encourage the development of oil and gas supply by subsidising technological development projects in the hydrocarbon production sector. It was known that the North Sea contained hydrocarbons, but there was no technology to exploit them. Offshore production in the United States was done at depths of 25–30 metres, while the North Sea has a depth of about 100 metres. The program has resulted in many important technological advances, which still largely determine the global level of oil and gas supply today. This programme has been characterised by the dynamism of European companies, their willingness and ability to innovate and create the cutting-edge technologies essential to the exploitation of hydrocarbon resources. Between 1974 and 1985, nearly EUR 500 million was allocated to this Community programme for a total investment of EUR 3 billion. Financial support for research, development and demonstration was provided in the following areas:

—exploration, including seismology – drilling

—production

—Enhanced recovery

—auxiliary vessels, submersibles, and navigation systems,

—robots that can work up to 500 metres deep

—laying pipelines

—pipeline transportation

—transport by ship

—Gas technology – Stockage

Of note is the development of directional drilling, i.e. it is no longer mandatory to drill vertically, but it has become possible to tilt the borehole when it is deep enough for it to penetrate horizontally into the reservoir and thus exploit the reservoir much more. This also makes it possible to reach tanks that are not recoverable from the vertical. For example, the first directional drilling project was carried out by ENI in the Adriatic Sea to exploit the Rospo Mare deposit.

All these technologies are now commonly applied around the world, including in the United States for shale gas and oil exploitation. But above all, they have made it possible to produce European hydrocarbons and thus drastically reduce imports from OPEC countries, with enormous consequences as we will see in the next section. Thanks to this programme, European companies have become and remain world leaders. Just think of the technological prowess of ENI or TotalEnergies in the Eastern Mediterranean, in the exclusive economic zones of Israel and Egypt. Note that the main beneficiaries of research funds were not the major oil groups, but service companies or independent bodies such as the French Petroleum Institute (IFP).

Unfortunately, the Maastricht Treaty paved the way for the ecologists in Strasbourg to kill this programme, which had created European flagships in terms of oil and gas technology.

The oil counter-shock

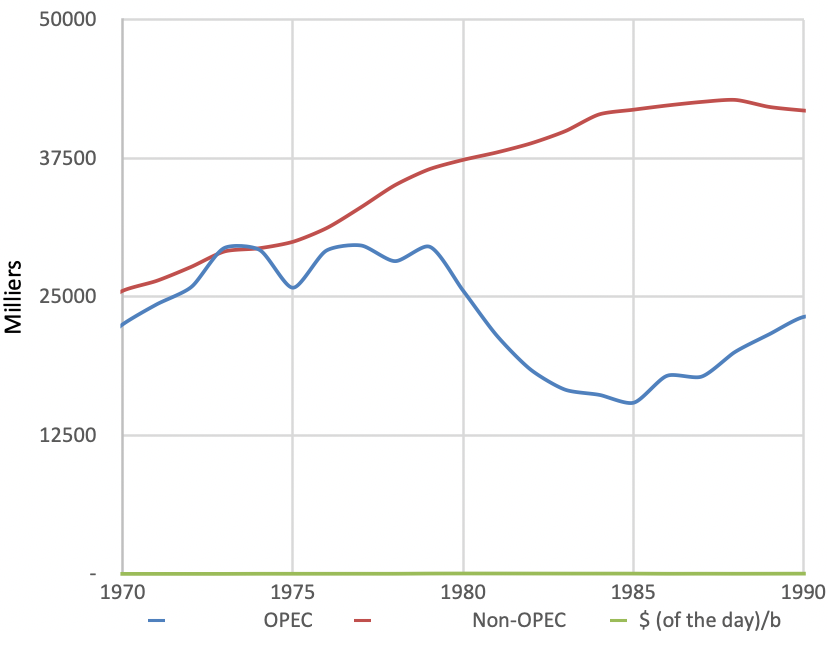

Each of these areas of the strategy has helped to free us from the geopolitics that the Arab countries were trying to impose on us. The OPEC countries have indeed been the victims of their strategy. From 1981, prices began to fall to $14/bbl in 1986 ($34 in 2021). The following figure shows that from 1979 onwards, OPEC oil production fell sharply and did not resume its upward trend until 1987. Conversely, non-OPEC production continued to grow strongly, so the gap between these two groups of producers became huge.

Moreover, with the abundance of the market, the price of crude oil fell, creating what has been called the oil counter-shock. This was a boon for the EC countries, but a disaster for the OPEC countries who sold less and cheaper, with the price of crude oil falling sharply from $37 to $14 per barrel.

It is therefore unsurprising that former Saudi Minister Ali Al-Naimi said in 2002, ‘Oil is not a tank. Oil is not an F-16. Oil is not a missile. It will not be used as a weapon. It is a source of prosperity.’

What can we conclude for our situation in 2022?

The slogan of the EU’s founders, ‘Abundant and cheap energy’ must once again become a priority; the denial of the current European leaders is incomprehensible. Anything that penalises its price must be fought with determination if growth is to be achieved, not as an objective, but because it is the only way to ensure full employment and to continue to improve living and health conditions. When one rightly complains about high health costs, it must be borne in mind that reducing energy prices means reducing energy prices. Energy is life and abundant and cheap energy allows everyone to live better. There is a strong social dimension to cheap energy. Energy poverty in the EU existed before the current crisis and is becoming more unacceptable.

Member States should take social measures to enable citizens and industry to ‘survive’ after this crisis. No one disputes that. But that won’t solve the problem. It would only cure him.

If the European Commission announced that fossil fuels – mainly natural gas – should no longer be ostracised as it has done in recent years, prices would fall as they did 40 years ago for oil. We saw how quickly this happened; it would happen again now. If we start producing our energy, geopolitical freedom would be restored, as it was during the oil counter-shock. There is no reason to sink into energy disaster. We have what it takes to come out on top.

We need to get back to technology promotion quickly and dynamically. Now, the EU only finances renewable energies and a little energy efficiency. The successes we have presented have been possible because European research was free and non-bureaucratic. Today, it is agency staff who impose research topics on researchers and companies. The research policy must be released quickly, as I have already requested.

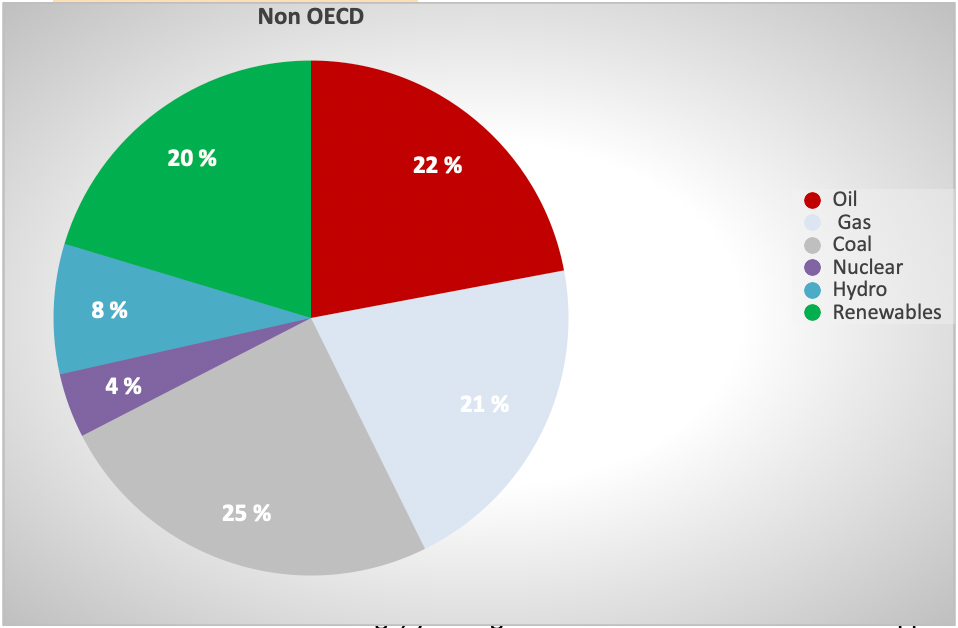

It is necessary to build on the European utopia which dreams that all energy production must quickly be supplied by renewable energies. They have their place, but they will remain limited. While for 49 years, long before we talked about climate change, we have been looking for alternative solutions, wind and solar energy represent only 3% of primary energy in the EU and worldwide. The rest of the world continues to rely on the energy sources we prevent ourselves from using coal, oil, gas and nuclear. Between 2011 and 2021, in non-OECD countries, only 20% of primary energy demand growth was met by renewables, so the gap between conventional and renewable energy is widening; contrary to what the International energy and the European Commission, the world is chasing conventional energies.

But what about climate change, you might ask? Ask those who have not stopped increasing their CO2 emissions since the adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Rio 1992): World: + 59%, Latin America: + 73%, Africa +93%, Non-OECD: +134%, India +280%, China + 311%, Vietnam +1380%. The EU may have reduced its own by 23%, but this is not the model that others intend to follow.

The EU will pay dearly for its unilateral energy disarmament.

Image par Dr StClaire de Pixabay

Further reading

“State of the Union vs green transition’s bad shape”, Samuel Furfari (Interview)

“The Ukrainian conflict reveals Europe’s energy fragility” Philippe Charlez (Interview)

Sustainable Energy Requires a Large-Scale Hydrogen Technology Boost