Last week, the German NGO Foodwatch published a report that intends to expose how the American soft-drink producer Coca-Cola is “marketing sweet causes of illnesses to children.” The report contains three main arguments, notably that sugary soft drinks marketed by Coca-Cola contribute significantly to the obesity crisis, that the company deliberately targets children, and that politicians therefore need to take concrete action against it.

The NGO starts out by displaying medical findings on the effect of sugary drinks, in order to underpin the seriousness of the argument. It rightfully treats the obesity crisis for what it is: a crisis.

But surely, Foodwatch would agree that even if they are bad choices, they are still OUR choices, right? It would be a phenomenal claim to pretend that consumers aren’t actually acting out of their own free will. And yet, this is precisely what its report does:

“This argument [that consumers are making choices out of free will] fails to recognise that our “free” choice is anything but free. What we eat and drink, and how much, is influenced by many external conditions […]”

The paragraph then continues to explain that advertising and marketing from early ages on have corrupted our free will. By that standard, it doesn’t become a debate which has much more of a capitalism vs. socialism shtick to it, it also begs the question what’s freely chosen at all. Did I freely choose to dislike the methodology of the Foodwatch report, or did a mysterious puppet master run a children’s show that implanted the idea in me at age 6? You’ll notice that here the argument becomes quite absurd. Casting aside all of behavioural economics for a vague notion of corporate control is not only unscientific, it’s lazy political agenda-setting.

As a political NGO, it was debatable how much peer-reviewed science Foodwatch would use in its report. The paragraph on the use of stevia in soft drinks is quite telling in this instance. They write:

“Although no negative effect of consuming stevia extracts is evident, its use is only useful if there is a health benefit over sweetened drinks. In the opinion of the French environmental and health authority ANSES this is not apparent. […] Therefore, it could not be a public health strategy to propagate the replacement of sugars in foods with sweeteners. Rather, it should be the goal to reduce the sweetness of food in general from very early childhood.”

In short, this means that even though scientific evidence points to no negative health effects of stevia, the standard of consumption MUST be that it generates positive effects. Therefore, even though stevia is a better alternative than sugar, it must still be the goal of public health authorities to reduce it. Throwing scientific findings carelessly out of the window in order to remain steady on the conclusion that all soft drink consumption needs to be reduced, is fundamentally ill-advised. Going into research in order to confirm an assumption you already had: that is confirmation bias.

Just as odd as the procedure of reaching conclusions from scientific evidence, is the Foodwatch claim that Coca-Cola deliberately markets to children. Reading this, all readers are certainly questioning if the American company is putting Cokes in strollers, given that “children” is mostly defined as being the stage of an infant an a youth.

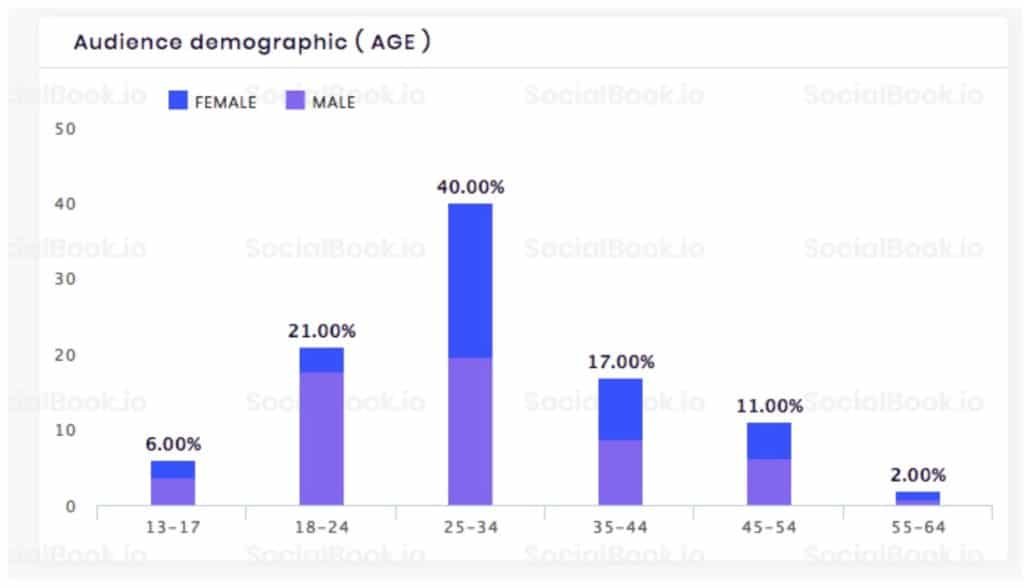

Foodwatch also points out that Coca-Cola has been endorsed by a certain set of YouTubers in Germany, as a part of a marketing campaign. Pretty damning you might think, until you notice that hardly any of them cater to children. If we take the performance of the YouTube star “Joyce” (1.2 million followers, 190 million views) as an example, we find very quickly that even the 13-17 year-old’s only make up 6 per cent of audience demographic, according to SocialBook.io:

These are YouTubers that often display explicit content or discuss topics that are not suitable for children; content which YouTube censors if the browser or app-settings are placed on the specific “restricted mode” designed for pre-teenagers.

This isn’t only a question of semantics, because the question of both “children” and “marketing” matters quite significantly to the core thesis of this report. In fact, it is the eye-catcher that is supposed to trigger the call to action. The report mentions “adolescent” 44 times, yet brings up “children” 136 times. However, the health claims are fundamentally more important if made about children before their teenage years, and it would be odd to fight child obesity by going after advertising that isn’t aimed at children.

Another example provided by Foodwatch is the 2016 Euro Football Cup sticker collection cooperation between Coca-Cola and Panini, as well as the Coca-Cola can collection of footballers:

“The campaign was the reason for the German Diabetes Association (DDG) and Foodwatch to file a complaint with the German Advertising Agency. Because according to the voluntary behavioural rules of the advertising industry, it is inadmissible to counteract the “learning of a balanced, healthy nutrition by children”.”

What Foodwatch’s report conveniently leaves out, is that its claim was rejected by the German Advertising Agency. The agency pointed out that the DDG and Foodwatch were mistaken in the allegation that the campaign was directed specifically at children and young adults. Its reviewers weren’t particularly convinced by the arguments presented, of which one presumed that the use of the German informal “Du” (“you”) was reason to presume that children were targeted. Unsurprisingly, Foodwatch reacted by questioning the credibility of the German Advertising Agency and accusing it of “protecting the junk-food industry”. This is the essential line of argumentation of this NGO: if you do not agree with our position, you must be in the pocket of big business.

What does Foodwatch argue for, in order to combat the problem of obesity? It demands that politicians take concrete action, including mandatory labelling, the restriction of “child marketing” (despite providing no evidence of its existence), and taxes on sugar. On the latter, Foodwatch wastes no time to explain the behavioural economics of its proposal, seemingly implying that the tax will automatically lead to a decline in consumption. While scientific findings differ on the effect, the Danish “fat tax”, introduced with a similar mindset, was repealed after just 15 months by the same political majority, notably because it was a failure. Social Democrat MP , presumably after reading the 105-page report, gave an interview to NDR a day after its release, agreeing on the need for a sugar tax.

The Coca-Cola report by Foodwatch is a case for paternalism, not a convincing paper for any specific set of political actions. The sheer denial that consumers have free will, really tells you everything you need to know about this NGO. Yes, it is undoubtedly true that individuals should watch out for their sugar consumption, and that parents should monitor the consumption of their children. Everyone agrees on this. What consumers will take issue with, is the idea that their choices aren’t made out of free will, and that it is upon the judgement of a handful of activists to determine their ideal lifestyle.

Consumers deserve choices. My choice is to label this Foodwatch report what it is: a call for paternalism, and nothing else.

This post is also available in: FR (FR)

“Casting aside all of behavioural economics for a vague notion of corporate control is not only unscientific, it’s lazy political agenda-setting.”

“Consumers deserve choices.”

These statements are in-congruent, behavioural economics repeatedly demonstrate how bad we collectively are at making decisions. Two of the most sited examples of interventions as a result of behavioural science are auto-enrollment in pensions and organ donation schemes. The whole point of this is the recognition that people will not make the correct decision either for their own or the greater good and removes the need for a choice to be made.

“….The sheer denial that consumers have free will”

As a result of my reading of behavioural economics I firmly believe that humans do not possess free will, at least not in the purest sense. We are easily manipulated and routinely unable to make the optimal decisions for our own benefit. Governing bodies need to begin to demonstrate an understanding of this and to introduce policy that could actually have an impact. The sugar tax (or the fat tax in Denmark) is not an application of behavioural economics and I believe these policies should not masquerade as such.

I do believe that the findings of this paper are true to form and alarming. The call to action falls flat. Personally, if the recommendations of NGOs or the actions of Government are deemed to be “paternalistic” I will support them as long as the are rooted in evidence with a clearly demonstrated rationale for the suggested intervention