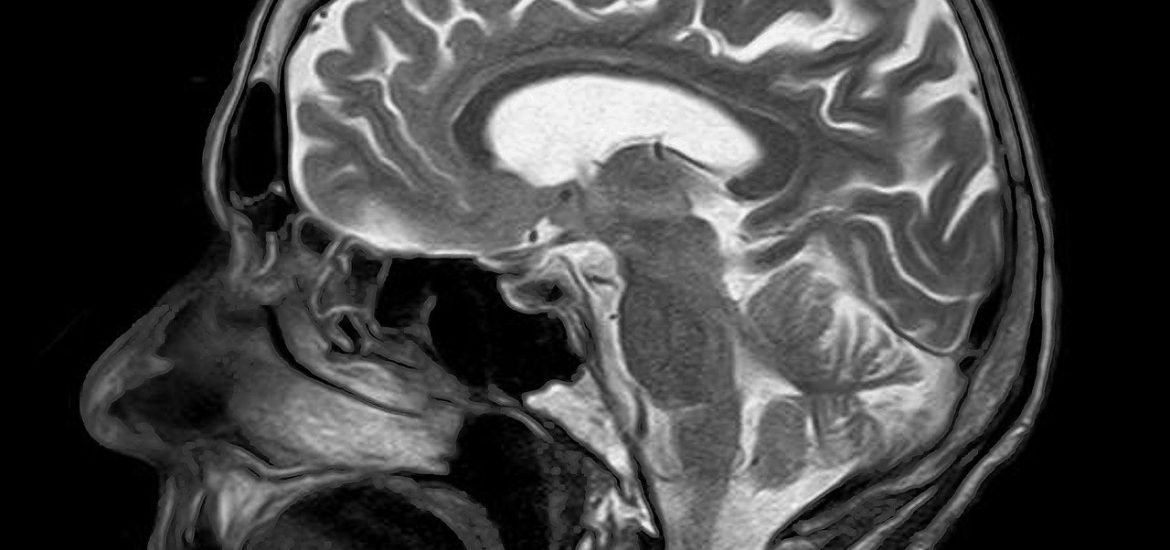

A team of researchers from King’s College London developed a new AI model to help radiologists identify brain abnormalities in MRI scans, including stroke, multiple sclerosis, and brain tumours, according to a study published in Radiology AI. The authors suggest that AI could address growing backlogs caused by shortages and the increasing demand for MRIs.

MRI scans are vital for diagnosing and monitoring a range of brain conditions such as tumours, strokes, and aneurysms. As a result, backlogs often lead to treatment delays and poorer patient outcomes. AI could be a valuable aid in easing pressure on radiology departments by triaging scans and increasing reporting speeds.

To achieve this, the team “showed” the AI model how to distinguish between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ scans. This was completed successfully and accurately, as compared with assessments by expert radiologists.

The AI system was then tested on specific conditions – using scans which weren’t included in the training data – such as a stroke, multiple sclerosis, and brain tumours. Again, it accurately recognised these.

Most AI models require large datasets manually curated by expert radiologists, which are expensive and time-consuming to produce. To overcome this, the team built an AI model that could train itself – without expert radiologist input – using over 60,000 brain MRI scans and their corresponding radiology reports.

“By training the system on scans and the language radiologists use to describe them, we can teach it to understand what abnormalities look like,” explained senior author of the study, Dr Thomas Booth, Reader in Neuroimaging at King’s College London and Consultant Neuroradiologist at King’s College Hospital.

The researchers also designed the model so that, when given a scan or a textual query such as ‘glioma’, a type of brain tumour, the system could retrieve similar cases, potentially supporting diagnostic review or teaching.

The authors suggest that the model could be used during scanning to spot abnormal scans and support radiologists in detecting potential errors in reports or in retrieving similar cases from past examinations.

The authors emphasise that this would speed up diagnoses and reduce reporting delays, thereby improving patient outcomes. “The next step is to run a randomised multicentre trial across the UK to see how abnormality detection improves workflows in practice. We are pleased to say that this trial will start in hospitals in 2026,” concluded Booth.